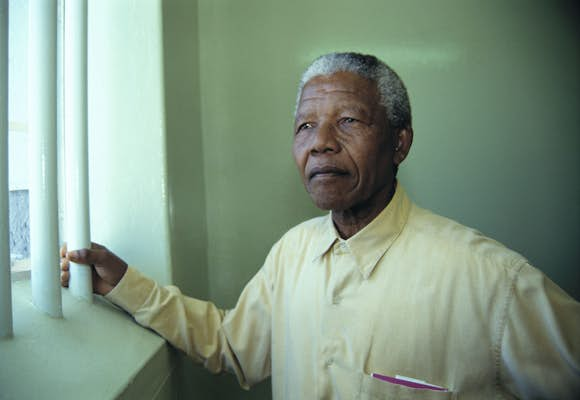

“I was 19 when I came face to face with Nelson Mandela,” Christo Brand writes in his memoir. Living with Mandela: My Prisoner, My Friend. “He was 60. Until that day I had never heard of him or his African National Congress. I was his prison warder on Robben Island and it changed my life forever.

The two men—one a young, white African prison guard, the other a charismatic African freedom fighter serving a life sentence—should have been bitter enemies. Instead, over the course of three decades, they forged a powerful bond that transcended age, race, politics and even death.

It’s not often that you get the chance to hear about Nelson Mandela’s life directly from the lips of a warder at his Robben Island prison. But since summer 2018, when he retired as manager of the Robben Island gift shop, Christo Brand has been offering private tours of the island’s prison off Cape Town. I’ve been a Mandela fan for decades, so when I met Christo Brand by chance, I knew I had to join him on tour.

Robben Island: A cold, inhospitable place

My private group tour started at the Nelson Mandela Gateway in Cape Town, from where we boarded a ferry to Robben Island. Upon first meeting Brand, I was immediately captivated by his ready smile and the kindness in his eyes. A gentle and compassionate soul who has had to deal with her own personal tragedy, Brand does not fit the profile of the stereotypical prison guard.

Robben Island is a windswept and mostly barren place where waves constantly crash against the forbidding shore in winter. Even in late summer, when I visited, the surf was pounding against the rocks. It was cool and crisp despite the bright sun, and I was thankful for my thin fabric sweater.

A former leper colony and prison near Cape Town (just 7km) offers wow-factor views of Table Mountain, but the water is so turbulent separating it from the mainland that escape is impractical. It is impossible. Brand told us he’s “wanted to leave since (he) got here, but (he) had to commit to at least two years.” As I looked up at Table Mountain on the rocky north coast with Brand and two others in my group, I understood why. The desolation was palpable.

Hard work takes its toll on Mandela and others.

After a stop at the Leper Cemetery, one of the highlights of our tour was the old limestone quarry. It was here that Mandela toiled for 13 years, digging and breaking stones. Forbidden to wear sunglasses, even in the unrelenting sun, prisoners were subjected to the blinding light reflected off the white limestone. Not only did the sun damage their eyes, but due to the dust clouds, they also suffered from breathing problems. “Mandela’s vision was affected throughout his life and the eye drops did not have much effect,” Brand said.

It is no longer possible to go inside the mine as it is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and has been cordoned off, but I clutched my chest with emotion as we stood in front of the mine listening to the brand. I could almost picture the prisoners, like in an old black-and-white movie, groaning as they tried to break the rocks, sweat streaming down their faces and dust billowing on their backs. Yes, the prisoners are suffocating and wiping in vain. The eyes

Mandela leads the introduction of prison education.

Despite the prisoners’ difficulties in quarrying stone, Mandela managed to convert the quarry, and eventually his section (B Section), into a classroom. The Red Cross provided him with works on literature, history, philosophy and political theory. The inmates will be given various texts, which they will later have to lead a seminar after reading. Initially the seminars were held secretly in one of the mine caves as being caught with the text was a big risk. But in time the African defenders allowed the seminarians on condition that they could listen to the talks.

Over time, prisoners won the right to take university correspondence courses and no longer had to hide their activities. They set up a library – essentially a bookcase in an empty double cell. “The boys appointed a librarian and there was a warder who would let them in two at a time. And each of them had a card to record which books they were borrowing.

Mandela spent much of his time studying in prison, taking at least fifty correspondence courses. “I used to say to him, ‘Why don’t you relax and take things easy? Why not borrow books from the library and enjoy yourself instead of pushing yourself so hard on all these exams?'” Brand said. , ‘If you have degrees, if you have knowledge – even if it’s about motor mechanics – they can’t take it away from you as long as you live.'” Mandela urged his fellow prisoners. “He would even tell us guards that we should get an education,” Brand said, “so that we can become thinkers and elevate our lives.” Warders began taking courses and, Brand recalls, “I saw inmates helping the warders with their assignments.”

Inhuman conditions and discrimination

Brand led our group into a former dormitory, a long, narrow room with a polished concrete floor and dimly lit windows. On display were sisal mats and rough, matted blanket wraps. We immediately remarked how cold the room was.

“It’s as cold as a refrigerator year-round,” Brand said. He directed us to a sisal mat spread on the floor with a thin blanket no more than four feet across. “It was just like that, except for three blankets,” he said. “No sheets, no covers, no pillows, nothing. Sometimes they could put their book under the blanket and use it as a pillow. They didn’t get mattresses until the 1980s.

“I’d be on patrol and I’d walk past Mandela’s cell and I’d see him doing sit-ups and push-ups and I’d ask him, ‘Why are you doing sit-ups at this time of night?’ He said, ‘Mr. Brand, I’m hot. Must do. I can’t sleep now. I need to warm up and try to sleep again.”

B-section prisoners, political prisoners who were imprisoned for life, “were treated worse than criminal prisoners,” Brand said. As if the cold wasn’t bad enough, there was shameful discrimination in the distribution of usable food. “The food on Robben Island was terrible,” Brand said. “And there was discrimination. Black people would get a bucket of porridge, no sugar, no milk, and a cup of coffee, no sugar, no milk. Colored (sic) The prisoners received a good quality porridge with sugar and milk, a piece of bread with white margarine and jam, and coffee with milk and sugar. Indian prisoners got a bit more.

The gift of human kindness

One of our last stops after visiting Mandela’s cell was the visitation booth, which was separated by a wall and had a viewing window slightly larger than A3 paper. Both parties had to speak in either Afrikaans or English as the meetings were recorded and it was a requirement that the prison staff, later listening, could understand.

Visits with family members, something prisoners looked forward to the most, were difficult not only for prisoners and visitors but also for sensitive warders like Christo Brand. “It was hard to tell them they only had five minutes left when they’d only been talking for 25 years and hadn’t seen each other in months.”

At one point Mandela’s wife, Winnie, got off the ferry on a rainy winter day wrapped in a large blanket. When Brand discovers that under the blanket is Vinnie’s four-month-old granddaughter Zulica, he is shocked. Despite all her pleas, Brand told her she had to leave the baby with the other guests. As he sat behind Mandela to oversee the visit, Winnie told her husband that she had brought her grandson but was not allowed to show him. Mandela begged to see the child, but Brand and another guard told him it was impossible. But Brand knew it was all wrong. Back in the waiting room, he asks Winnie if he can hold the baby and quickly disappears. He went back to the visitation booth and took the baby to Mandela. “She held him and just said, ‘Oh,’ and I saw tears in her eyes as she kissed the baby,” Brand said.

Only Brand and Mandela knew what had happened. Mandela thanked Brand, knowing that the warder could have lost his job and himself lost his privileges. “This moment that passed between us, this quiet understanding, was very special to Mandela,” Brand said. “After that moment, we became allies for life.”

Robben Island: Now a symbol of hope and reconciliation.

On the packed ferry back to Cape Town, I pondered the irony of Robben Island: an island that once represented everything most reprehensible about apartheid, today hope and reconciliation. as well as a UNESCO World Heritage Site symbolizing his victory. The human spirit on suffering. I thought, too, of the unlikely friendship between Brand and Mandela, and the strange twists of fate that brought them together. Mandela and Brand remained close friends until Mandela’s death.

As the boat approached the Nelson Mandela Gateway, I concluded that the special bond shared by Mandela and the brand perfectly embodied the spirit of hope and reconciliation.

Practicals

The fee of A private tour with Christo Brand is R6000 (US$407). Note that this is a guiding fee only and a set fee regardless of numbers and is subject to COVID-19 restrictions. Island ferry tickets, private vehicles and drivers are booked directly from Robben Island. Access to Mandela’s Cell depends on group size and is not guaranteed (standard group tours never have access to Mandela’s Cell). The Brand Tour offers exclusive access to the solitary confinement home of Robert Sobukwe, another prominent South African political dissident and founder of the Pan-Africanist Congress.

You may also like:

Top 10 Nelson Mandela Sites in South Africa

Cape Town’s controversial (and free) public art

The National Museum of African American History launched an online resource to talk about race.